A Cotton Print Gown for a Young Lady,

1750-1790

It is often the young girls who are the ones most fascinated by seeing the clothing we ladies wear to reenactments, and the girls who are the most excited when you offer them the chance to handle a gown, test out a fan, or try on a hat. But the question always arises, "Would little girls like me get a dress like this, too?" I have a small collection of images of 18th-century children that I bring with me to our non-battle public reenacting events, demonstrations, and "shows," but I always wanted to make a representative girl's gown to be able to give these inquisitive young ladies a real glimpse at what their counterparts wore centuries ago.

With a special local historical society event this past weekend, I decided it was the perfect time to finally get around to making something suitable, and I'm so glad I did! The reaction it got from all the young visitors was priceless - added to which it also offered the perfect photo opportunity! It was so, so precious watching these little ones fall in love with historical fashion. :-)

The pattern: Not having a child of my own to draft a pattern on, and having examined only a handful of extant children's gowns myself, I decided that going with a pattern for this project would be the best way to assure I achieved the proper shape and proportions. There are surprisingly few options out there when it comes to gowns appropriate to girls and pre-teen young ladies, but based on the original pieces I've examined, and on images I've looked through online, I opted for the

Mill Farm pattern, which gives an accurate and representative shape appropriate to girl's gowns worn between about 1750 and 1790. I made some changes to the pattern based on my own research, which I'll detail below, but these were more or less minor.

Inspiration: I wanted to make an everyday gown for the child of a lower-middling family, which would represent the majority of CT families (mostly farmers) during the Rev War period. My primary inspiration for the fabric choice was a "blue and white sheled" cotton/linen textile currently on display in the

"Threads of Feeling" exhibit. It's included in the

Threads of Feeling book as figure 33, on page 41. The child admitted with this token in 1759 was a girl, and I was delighted to find a brand new fabric that had been recently released that fit the bill quite satisfactorily. More specifics on the fabric are below.

Extant children's clothing is, predictably, rare because it would typically have been worn by multiple siblings until it fell apart. I did, however, have two main inspiration originals for this project. One was a brown wool gown dated to the 1740s in the collection of the Met Museum. The Costume Design Center at Colonial Williamsburg did a reproduction of this gown (right down to all of the piecing details) and had it on display during the

"Reconstructed Visitable Past" conference several years ago, so I had a chance to examine it closely there.

Image linked from the Met Museum of Art online collections database.

Image linked from the Met Museum of Art online collections database.

The other was a cotton print gown in the Philadelphia Museum of Art dated to 1780. This gown has some curious details, including the mock laced-in stomacher and the flaps at the sides that (one suspects?) might cover the pocket openings, or simply reflect the peplums of jackets that were increasingly popular in that decade. There is no back view available, so you can't tell how far these pieces extend around the back, nor how the gown is fastened closed.

Image linked from the Philadelphia Musem of Art's online collections database.

Construction details: The

Mill Farm pattern was clearly written with an experienced sewer in mind, so the directions were correspondingly limited when it came to specifying stitches and similar details. This basically leaves construction methods up to the sewer, so I opted to put my gown together using the documented construction techniques I use on all of our adult gowns. First, I assembled the sleeves as usual, opting not to include tucks in them, following the Philadelphia Museum inspiration source, though you do sometimes see two or three sleeve tucks in period images of cotton or linen gowns.

The bodice lining was done in the same way as a typical gown lining, turning the edges of outer fabric and lining in on each other to finish the neckline. The sleeves were also inserted in the "usual" way, which got a little complicated because I didn't have a child's shoulder to fit them on, so I just fiddled with the sleeve cap pleats until they looked good to my eye and then double-checked to see how close my fit was to the pattern's. I then top-stitched the shoulder straps down to cover the top of the sleeve, in the same way as you would for a woman's gown.

The skirt of the gown has three growth tucks along the bottom. The couple of originals I've looked at had very deep hems instead of the growth pleats, but you do see a lot of tucks in children's gowns in portraits and I prefer their look to the deep hem. It's also much easier to let out a tuck to lengthen the gown than it is to unpick the hem, let it down, refold it, and then hem it all over again.

Three growth tucks are at the bottom of the skirt.

The pattern did not include pocket slits, but I added some because the kids who visit our events love learning about tie-on pockets and speculating about what they might have kept in them if they lived "back then." Because I added the slits, I opted to pleat the skirt to the bodice instead of gathering it, as the pattern calls for. Both methods are documented, but I preferred the pleats to help accentuate the pocket slits. They're angled in the same directions as they are in the standard 18th century petticoat.

The back of the gown laces closed with two hidden eyelet panels sewn into the back of the gown to allow for greater adjustability, a feature I copied from the Met original. The pattern includes criss-crossed lacing, but I changed it to spiral lacing to reflect the lacing pattern on that same extant Met piece. I also liked the idea of the spiral lacing mimicking the conventional lacing style of stays.

The gown laces closed in the back using two concealed lacing

strips supported by two pieces of boning.

Spiral lacing up the back.

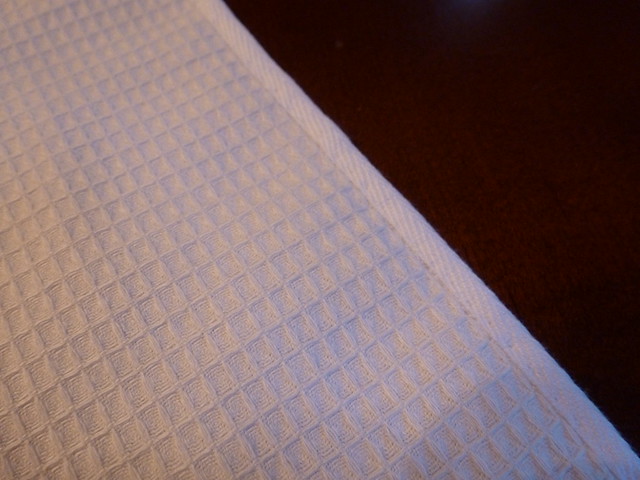

The fabric: As I mentioned above, the inspiration fabric was a "blue and white sheled" cotton/linen textile token from "Threads of Feeling." While monochromatic arched "shell" prints and motifs were very popular throughout the second half of the century, particularly amongst the lower classes, there are few options available now in terms of comparable modern fabric. Duran Textiles offers a document

reproduction of an original shell print that lines a 1760-1780 banyan at Winterthur, but this was a tad out of my price range for this project. Instead, I opted for a new print recently released by

Wm Booth, Draper that was inspired by multiple shell prints. It's a very nice quality and a lovely weight and looks adorable made up into the gown.

Finishing the look: A young lady wearing this gown would have worn it over a shift and perhaps over stays, though as the century worn on, younger girls tended to wear stays much less frequently than they had in the past until they reached puberty.

Inspired by one of my favorite period paintings of a child, Chardin's

Une petite fille jouant au volant (1741), I'm planning to complete this display item by making a white linen pinner apron to pair with the gown, as well as a smaller set of child's pockets and a child's cap.